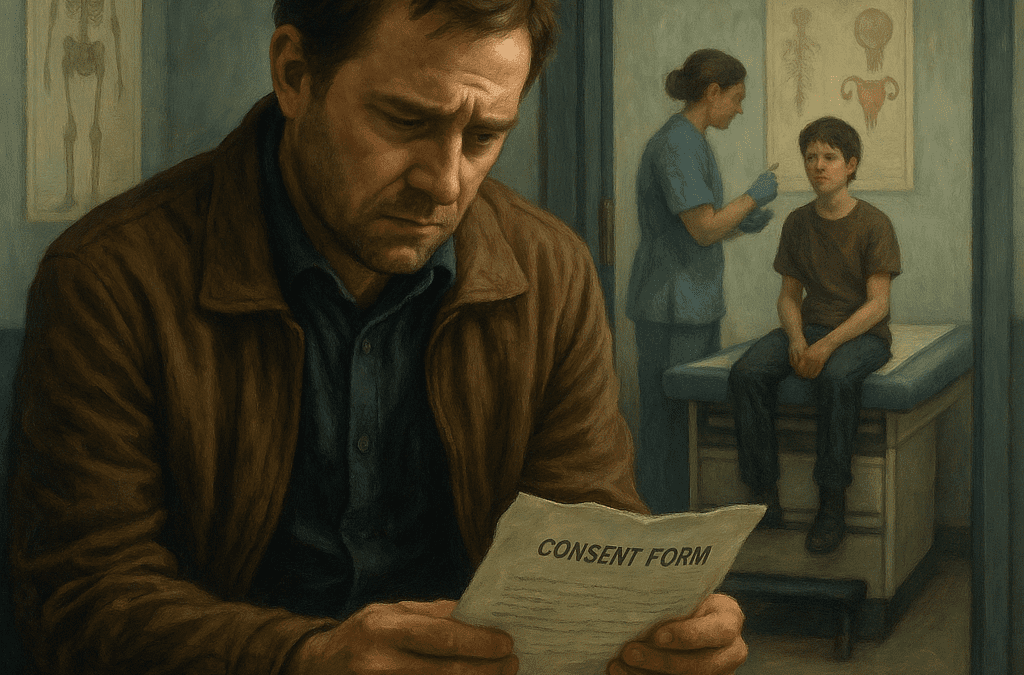

When my daughter first told me she wanted to pursue gender-affirming care, I wanted to be supportive. I love her unconditionally, and watching her struggle with identity has been heartbreaking. But as a parent, my job is not just to support—it's also to protect. And as I've learned more about testosterone replacement therapy and its effects, I find myself with questions that keep me up at night.

The Irreversible Changes

The word “affirming” sounds so positive, so gentle. But what I've come to understand is that testosterone therapy brings permanent, life-altering changes to a developing body. These aren't like trying on different clothes or experimenting with a hairstyle. These are fundamental biological shifts that cannot be undone.

Voice changes happen relatively quickly and are permanent. My daughter's voice would deepen, and that change would remain even if she later decided this path wasn't right for her.

Fertility is another concern that weighs heavily on me. At her age, she can't fully grasp what it might mean to lose the option of biological children. How can any teenager truly understand that choice when their brain is still developing, when they haven't experienced the full arc of life and how our desires evolve?

Skeletal changes occur during puberty when growth plates are still active. Testosterone affects bone density and structure. The intervention happens during a critical developmental window that nature designed specifically for this biological transformation.

Body hair, facial hair, and other physical changes that develop are largely permanent. The redistribution of body fat, muscle development—these reshape the physical form in ways that persist.

The Research That Troubles Me

I've been reading the medical literature, trying to understand the outcomes. What I've found doesn't give me the reassurance I'm seeking.

A study following individuals for 18 months after starting hormone treatment found that pre-treatment mental health symptoms and social support didn't predict life satisfaction outcomes. In some ways, this seems positive—it suggests that those struggling beforehand can still benefit. But it also raises questions: if we can't predict who will be satisfied, how can we be certain this is the right path?

Research on romantic relationships shows that transgender individuals and their partners face significant challenges, including difficulties with disclosure, societal expectations, and identity questions. About half of relationships end during transition, with 54% of those endings directly attributed to the transition itself. This isn't about judgment—it's about recognizing that medical transition affects every aspect of life, including intimate relationships.

Perhaps most concerning, a systematic review of regret after gender-affirmation surgery found that while overall regret rates were low at 1%, the reasons for regret included poor surgical outcomes, social difficulties, and unrealistic expectations. Some individuals experienced what researchers call “true regret”—feeling the surgery was not the solution they believed it would be.

The Complexity of Dissatisfaction

The research reveals that dissatisfaction isn't always straightforward. People may experience regret due to surgical complications, aesthetic disappointment, loss of physical sensation, ongoing stigma and discrimination, lack of family support, or mental health challenges including pre-existing conditions like depression and anxiety.

What strikes me is how many of these factors are about the world around us—discrimination, family rejection, social isolation. Studies show that minority stress, stigma, and lack of acceptance significantly impact relationship quality and mental health for transgender individuals. Are we addressing the root causes, or are we medicalizing a response to social prejudice?

The Weight of Childhood

My daughter won't experience a natural childhood in the way most people do. She won't go through puberty as her biology intended. Instead, she'll navigate a medical process with regular appointments, blood tests, hormone management, and the psychological weight of such significant decisions at such a young age.

Research indicates that high levels of anxiety and depression are common among individuals awaiting treatment, though these don't necessarily predict long-term outcomes. But what does it mean for a child's development to spend their teenage years in this state? What are the long-term psychological effects of blocking or altering one of the most fundamental biological processes?

My Questions as a Father

I don't write this from a place of judgment toward my daughter or others facing these decisions. I write from a place of love and deep concern.

- How can we ensure informed consent when the person consenting is still cognitively developing?

- Why are we so quick to medicalize what might, for some, be a phase of exploration?

- What happened to watchful waiting, to therapy that explores rather than immediately affirms?

- Are we truly prepared for the possibility that some young people will grow to regret irreversible changes made in adolescence?

Recent research notes that mental health issues should be addressed separately from transition, rather than being barriers to it. While I understand the reasoning—we shouldn't discriminate against those with mental health challenges—isn't it also reasonable to ensure someone is in a stable mental state before making permanent physical changes?

Where Do We Go From Here?

I love my daughter. That will never change, regardless of the path she chooses. But love doesn't mean abandoning caution. Love means asking hard questions, even when they're uncomfortable.

The research shows that most people don't regret transition. But “most” isn't everyone. Among those who do experience regret, many cite social factors, unrealistic expectations, and medical complications. For those individuals, the damage is done—changes that cannot be undone, choices made in youth that have lifetime consequences.

As parents, as a society, don't we owe it to these young people to move more slowly? To provide comprehensive mental health support? To address the social discrimination and lack of acceptance that drives so much distress? To acknowledge that adolescence is a time of change and exploration, and that sometimes the most loving thing we can do is give space for that exploration without immediately making it permanent?

These are the questions that keep me awake at night as I watch my daughter navigate this path. I don't have all the answers. But I believe the questions themselves are important, and that asking them comes from a place of love, not rejection.